- Home

- Mike Barnes

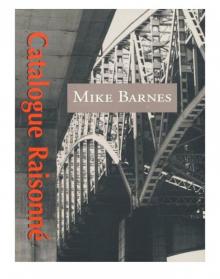

Catalogue Raisonne

Catalogue Raisonne Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

I - Secrets of the Surrealists

I

2

3

4

II - CHOP

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

III - Secrets of the Surrealists

21

22

IV - CHOP

23

Copyright Page

to John Metcalf

Catalogue Raisonné, mixed media, 238 pages excl. cover, provenance unknown. Gift of an anonymous donor.

Materials Used

Gallery Administration:

WALTER, Director of the Gallery

BUD, Assistant to the Director

BARBARA, Head of Education & CommunityOutreach (ECO)

NEALE, a tall Curator on loan from Toronto

PETER, an Art Conservator

JASON, a Registrar

ANGELA, a receptionist living with Paul

Attendants:

HANS (“The Führer”), Head Attendant, a small

capable German

RAMON, assistant to Hans, a handsome DJ

SEAN (“Mumbles”), a balding bard

PAUL, a chess player and former rhythm guitarist for

The Chile Dogs

LARS & LEO, called “L” for convenience, twin sons of

a Danish businessman and a former Miss Bangkok

Burns Security Guards:

ROBERT, a chess player and composer

OWEN, a bachelor and collector of Philip K. Dick

TED, a married man and multiple father, a collector

of Isaac Asimov

STEFAN, a scrupulous replacement

FRANKENSTEIN, a trainee

Others:

MRS. SOAMES, an elderly volunteer

PICCONE, a businessman, owner of The Tulips

Gentlemen’s Club

RICK, a bouncer

CLAUDIA, an unemployed artist, sister to Robert

ARMIN, an old chess player

Donors, Friends, Sponsors, Benefactors, Volunteers,

Patrons, and Citizens.

The piece comprises 7 weeks in spring, 1984, in Hamilton, Ontario. It is subdivided into 4 sections, with dimensions as follows:I. Saturday, April 14.

II. Sunday, May 13 to Tuesday, May 22.

III. Thursday, May 24 to Monday, May 28.

IV. Saturday, June 2.

I

Secrets of the Surrealists

I

Hans and I were hanging pictures in the Braithwaite Galleries when Bud came back to tell us that we needed new clothes. Hans checked his hammer mid-swing and let his mouth fall open, as if someone had just told him Berlin was burning. As apparently, when he was nine, someone had.

“It’s the bloody eleventh hour,” he said to Bud, without taking his eyes off the grey marks we’d made on the wall.

“Yes, well, er . . . .” Bud blushed, and flicked a glance at me. Then at Peter across the room, making a show of checking the straightness of the little Tanguy he’d just hung. Peter, the gallery’s conservator, stood a prim two paces back from the wall, desert boots tight together, perfectly still. All power to the eye. It was the usual pantomime – Hans a level man, Peter confident of his eye; both of them still passionate about the issue, so needing to work well apart – but this time it seemed to help Bud find his voice.

“We’ve decided you need new uniforms for the opening,” he said firmly, but to me.

I was standing beyond Hans with level in hand, close to the Dali that Neale had leaned in its position. Hans used a two-man system (whereas Peter could hang alone, at least with small works): after he banged in his nails and hung the painting, I leaned in with the level, which Hans consulted as he tugged down on one corner or the other. Then on to the next painting, where he reeled out his tape measure from the floor to the prescribed height, to which I lifted the work; Hans with the level now, we found a preliminary balance; then I pressed, pressed and jiggled a bit to make the grey marks. It worked. But Peter couldn’t be disputed when he said he was faster. Hans began hammering.

Bud frowned, then looked over his shoulder to find Walter. The director was in the smaller Braithwaite Gallery, looking at the catalogue with Neale, his face in quarter profile to us. But he must have had some sense of a disturbance, because he drifted over. Walter’s attention was an uncertain thing. He had a drift, a saunter, but also a quick trained eye. He’d taken just one short stroll, his first visit to the show, when Neale was placing the paintings. It might have been respect: Neale had curated the surrealist show, it was his baby, his coup. When Walter was about halfway across the room, Hans stopped hammering. Turned for the first time.

“What’s up?” Walter said. As if nothing much really could be.

Bud told him about the new uniforms for the attendants. “Barbara feels the old uniforms are tacky.”

“We-ell. No argument there.” Brief glance at the ones Hans and I were modelling.

“We’ve still got the whole show to hang,” Hans protested. “Then those changes in the McMahon Gallery you requested. I’ve got to give the boys at least a few minutes for dinner. Clean-up, then all the Gala preparations. . . .” Hans gestured provocatively with the hammer, but his face looked wan and tired, anticipating rebuff. I watched Bud and Walter hear him out. Bud’s fair skin still had some rose in it, but his stiff shoulders had relaxed since Walter’s arrival. Seeing the two of them standing together – Walter tall, silver-haired, in a good dark suit; Bud short and cherubic, in brown leather pants and thin leather tie, a yellow shirt – you felt there might be an evolution taking place. Over time, the one could become the other.

“We-ell now,” Walter said. The drawl he brought out when smoothing things was a mystery, since he’d grown up in Thunder Bay. He shot his cuff and checked a silver watch. “There’s still four hours till the big opening. Couldn’t we have cut it a bit finer?”

Bud and he exchanged a look that seemed to calm Bud further. Hans stared at Walter. Fourteen years of working for him, though he judged him a “good enough director . . . a fair employer,” hadn’t helped him to appreciate Walter’s irony. Probably nothing could.

“Still plenty of time for a wardrobe change,” Walter said.

Hans snapped. It may have been just strain and tiredness; perhaps it always was, mainly. Hans worked with an immigrant’s grateful ferocity, but could also lapse into outraged cursing at the slightest provocation. The question of his mental state was a common gallery coffee topic, especially among the upstairs people, but perhaps there was nothing really wrong with him besides overwork and being from another place and time.

“No, goddam.” He raised his hammer. “Not this time. With all this work to be done, go and get new clothes. For some bloody Gala. No.”

Walter watched him carefully, not letting more than a gleam in his black eyes betray a desire to fire or kick the man. “It’s okay, Hans,” he said.

Hans began gently tapping the nail with his hammer. A prelude or a concession. Anyway, his final answer.

“Where’s Ramon, Paul?” Walter asked me.

“Getting the Martin and Rogers, I think.” Just as we’d started hanging the surrealist show, Walter had decided changes were urgently needed in the contemporary Canadian selection hanging in the MacMahon Gallery, our largest viewing space and adjacent to the Braithwaite Galleries. “Need a proper setting for the jewel,” he’d murmured smiling to himself. But

while it was true patrons would have to pass through the MacMahon on their way to the surrealist show, it piled on more work at an already hectic time, and made us feel, as we shuttled between Neale and Walter, that we were serving two competing midwives, each determined to focus resources on her delivery.

“Not the Bolduc?” Walter said.

“It’s already up.”

“O-kay. All right, then. Round up the others and go over to the mall. Tell Ramon to put it on the gallery’s account at Sears.” To Bud: “I assume Barbara’s got her colours picked out.”

Bud nodded. And that look – knowing, faintly amused – got exchanged again.

Bud handed me the gallery’s Sears card and I turned to go. Hans stopped his tapping – more like actual hammering now – long enough to say, “What about gallery security?”

Walter looked slightly pained. It might have been a silly question. In the galleries not actually cordoned off, other gallery personnel were working, hanging pictures and lighting them and getting ready for the Gala Preview. Volunteers were delivering platters of hors d’oeuvres, bunches of flowers, wines and cups and plates. There were about six actual patrons, most of them teenage girls waiting to catch a glimpse of Ramon. But like a lot of silly questions, it required an answer.

“Leave an L,” Walter said, not raising his voice despite Hans’s sounds, which were bangs now. “They’re the same suit size, right?” Smiling at the elegance of his solution, he strolled off toward the MacMahon Gallery, probably to check if I was right about the Bolduc.

I was about to go find Ramon, when I noticed Bud looking uncomfortable again. His shoulders had stiffened up, his hands fidgeted near the square end of his tie. In the silence when Hans had done his nail, which required several corrections from each side, Bud said, “Hans, we’ll need to know your size.” Bud’s voice could break a bit at times, too.

“Thirty-eight short,” barked Hans, his lips white around another nail.

Meanwhile Peter had briskly finished another painting and was starting on a third.

Neale was still reading his catalogue when I passed through the outer Braithwaite Gallery. He gave no sign of noticing me. Even when you stood in front of him, Neale’s gaze roamed above and around you, or else passed right through you, like an X-ray seeking a blocked painting. Very tall and thin, balding spikily, he stooped slightly as he read, as if shielding the sculpture pedestal with the Comments book anticipatorily chained to it. I stepped over the rope blocking off the gallery. Just beyond, in a brightly-lit corner of the MacMahon, the hippy silk-screen artist we used for big shows was doing the title lettering on a divider panel laid flat on a sheet of plastic. He had his wooden rectangle stretched with fine mesh positioned on the panel. A part of the mesh was inked, and he was pulling a short squeegee carefully across it. His abundant long hair, which flopped bushily when he came to try to sell his prints, was tied back tightly now.

Farther out in the main room, Ramon was lighting the Ron Martin. Lush, lazy-looking swirls in all-black, like fan turns. One of Walter’s favourites. Ramon was up in the highest part of the gallery, the section cut through to the second floor. The extension ladder out full, jouncing with his smallest shifts as he adjusted the flaps on the lights. Even if Ramon hadn’t been the best lighter in the gallery, no one else was willing to work up on those tracks. You felt the swaying ladder always about to snap, though as yet it never had. At the bottom, his gallery groupies were making small cries of alarm. “Oh, Ramon . . . Ramon, be careful. OH!” Giggling in between moans and gasps. Young bodies tight in jeans and T-shirts, pretty even through the caked makeup. Lars and Leo were trying to distract them with stories of their own heroism atop ladders. Perils impossible to imagine, even if the twins’ parents had not been identified as Sponsors on the board in the lobby. Still, since Ramon was occupied, they got some attention. Though not in Ramon’s league, they were, females from twelve to eighty agreed, “very cute”.

Ramon made a face when I called up the new errand to him. He climbed down the ladder. Louder coos of “Careful, Ramon . . . ooh!” Lars and Leo importantly bracing the bottom.

“Hans said it was okay?” Ramon asked, smoothing his dark hair back from his forehead.

“Yeah, does the Führer know?” In chorus.

“He heard about it,” I said. Ramon smiled. With his runway looks and easy fashion sense, he was the natural man for the new-suit detail.

Lars and Leo became frisky, pushing each other, foppishly boxing, when they learned one of them would have to stay behind as gallery security. It was Tweedledee and Tweedledum cast as two cute nineteen-year-olds of Thai-Danish mix, working part-time in the gallery until they could credibly play a part in Carlsson Interiors, the family Bathroom & Custom Kitchens business. The girls snickered. “You stay. No, you stay.” I helped Ramon put some of the lights he’d tried back in the box. Black box lights with hinged sides, a strangely sooty dust that came off on your hands. Then Lars – I was fleetingly sure it was Lars – must have realized that staying would mean a half hour of unshared face time with the gallery girls. “I’ll stay,” he said, feigning resignation. But the minds were as identical as the faces, and the other – now I wasn’t sure again – said, “No, me. I’ll stay, Ramon. Ramon, me.”

“Hey!” Ramon never shouted, but he had a neat trick of deepening his voice while raising it slightly. “Which one of you is supposed to be on the desk?”

The boys shared sheepish grins. They might not have remembered. Front desk to them was a boring, lonely exile in the lobby, to be abandoned at the first opportunity. Whereas Ramon and I – both nearing thirty, with ten years and four on the job – welcomed that half hour in the rotation as a quiet respite, time off your feet. Smokes and phone calls for Ramon. Magazines or deep thoughtless breathing for me.

“Go on! Go back!” Ramon brandished his black lights at them. And the boys – and girls – with scared pleased faces, backed toward the lobby. “Animals!” he muttered at me. “Incompetents!” Rattling his lights, he took a few mincing steps, mincing and stamping. Like an old lady shooing cats. But even being ridiculous, Ramon managed to look good. Natural cool. It was a pure gift. With squeals the teens dispersed. But a few seconds later were edging back in again. Ramon sighed. He prepared to wheel the dolly with the light boxes to the freight elevator. “Go find Mumbles,” he told me.

“Who’s Mumbles?” I heard a girl say as I walked away.

“Mumbles, you know. That weird bald guy? Sean.”

Sean was never hard to find. Unless otherwise directed, and sometimes even then, he would be at the furthest gallery remove from everyone else. I found him on the second floor, pacing the U-shaped mix of corridors and back gallery that overlooked the main space. He came at me down the Soames Sculpture Hall, his lips twitching, his eyes wild. The brown polyester uniform, which looked merely awful on the rest of us (only bad on Ramon), looked as if it had been used as a duster and then thrown at Sean. A stranger would have seen a homeless man rushing at him, muttering. I saw my colleague of almost four years (he was hired right after me), whose chafing neurosis would probably never rise to the level of madness, composing poetry.

“Fucking shopping expedition. Buy the Emperor new clothes. Make the man.” Sean grumbled into the space between me and a large potted ficus that needed watering. If Hans’s gallery venting was sudden and explosive, Sean’s came out in a slow constant leak. He was forever denouncing the gallery and all its holdings and doings, perhaps mainly because they interfered with his concentration. I don’t believe he would have been much different any place he worked. And he was forgetting now that one of his favourite diatribes involved the itchiness and “demeaning decrepitude” of the brown suits.

I leaned against the wooden railing, staring down at the wide staircase I’d just come up. You had to give the venting time to expire; you couldn’t rush it.

Sean leaned and glowered a few feet away. “The Grand Staircase. Now why grand, exactly? It’s a staircase. And why Gala Pre

view, pray? Wouldn’t Preview have been accurate?

“What does ‘gala’ mean exactly? You hear a word all your life and then – ”

“It means another excuse for the wankers to congratulate themselves.”

I looked sideways at Sean. If he was staring fixedly at something, like a staircase, he would tolerate this. He’d once said, speaking of the full-time guards (though L would not have altered his opinion), “We aren’t a pretty picture. Sometimes I think we’re a kind of freak show ourselves. Huh? No, not a rogues’ gallery. Not that dashing or dangerous. More like a performance piece arranged by someone in the gallery.” Given Ramon, Sean was obviously putting some extra spin on the word ‘pretty’, but I could see what he was getting at. When Bud had phoned me, after I’d spent six months looking for work in the recession of 1980, I thought I’d landed a dream job. Strolling and looking at slowly changing artworks, telling forgetful seniors and mischievous children not to touch them. I thought the space and time might even float me back to songwriting. But it was amazing how quickly the hours of pacing the beige carpet wore that down. Something about the stillness, that museum hush. Broken at intervals by petty squabbling – turf wars over uniforms, flower arrangements, cushion colours – that I overheard or had reported to me by Angela if they occurred up in Administration. All for the sake, supposedly, of a minuscule number of patrons – fewer than twenty a week sometimes, if you subtracted the gallery groupies and the school and seniors groups led around by the docents. Shockingly quickly, I’d learned how to pass several hours without thinking anything. And not seeing or hearing a whole lot more.

Still, in the not-pretty picture we were presenting, Sean would have to be Exhibit A. His pale skin was blotchy, with pebbly red patches that sprang out from bad temper or scratching, or maybe allergies. His head resembled Renaissance depictions of Fortune, ideally bald in front, with long frizzy hair in back. Except with Fortune, the hank of hair hung at the front, so you could grab it on approach if you were wise enough. He also looked like Old Father William, Tenniel’s drawing of him in Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll’s character was old and fat and silly, while Sean was thirty-two and only slightly plump. These allusions and their limitations Sean had supplied himself; no one else had read enough to do so. He might have been hoping to spark a better nickname for himself than Mumbles. Though that name was unavoidable, as everyone had seen his lips moving as he paced, composing a long epic poem that would, he claimed, “unite Blake with Yeats.” Over one hundred stanzas so far, he said. No one had seen or clearly heard a word of it. No one would, he said, until it was ready to be “hatched upon the world.”

The Reasonable Ogre

The Reasonable Ogre The Adjustment League

The Adjustment League Catalogue Raisonne

Catalogue Raisonne